BOOK REVIEWS by Sylvia Elias, British Columbia, Canada

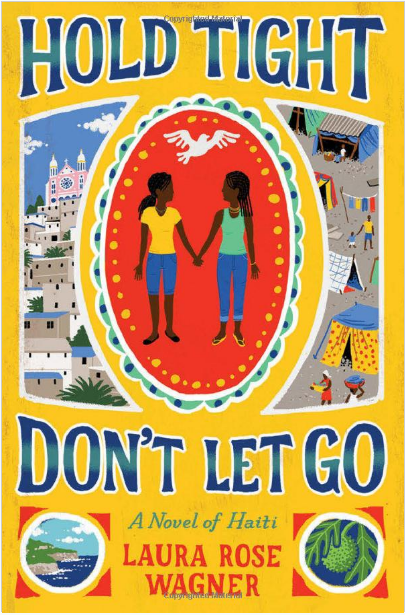

I’ve come to believe that Haiti provokes passion like no other place on earth. To support this, I give you two stunning novels by highly diverse authors: Claire of the Sea Light, from the brilliant mind of the venerable Haitian-born writer Edwidge Danticat; and Hold Tight, Don’t Let Go, from the insightful new voice of American Laura Rose Wagner.

I’m not a book reviewer – just a new Creole learner and a person who deeply loves books for the worlds revealed therein. Haiti, in all her beauty and horror, her suffering and triumph, comes alive in these novels.

Danticat opens her novel with the disappearance of a fisherman at sea before introducing Nozias, a similarly poor fisherman who makes the heart-breaking decision to give away his motherless daughter, Claire Limyè Lanmè, to a wealthy woman. He seeks for Claire the life he cannot provide for her from the dwindling resources of the sea.

Aware of what is afoot, Claire disappears. As neighbors and friends search for the missing girl, a diverse cast of characters is revealed, through deftly forged stories of Haitian life. Danticat is a fearless writer. Like a painter, she creates first a bold backdrop of life in the village, and then carefully, perfectly, layers themes of friendship, death, love, poverty, hope and dignity on this canvas.

Laura Rose Wagner’s wonderful Magdalie will quickly capture your heart. Magdalie’s aunt, her adoptive manman, dies on January 12, 2010. In an instant, Magdalie’s life shatters, as did the lives of millions on that dreadful day. How does a 15-year old schoolgirl in Port au Prince reconstruct a life, when she’s barely old enough to understand what life means?

Wagner’s writing style is completely different from Danticat’s, yet she brings to life her characters with the same compelling clarity and honesty. Readers will cherish the connection between Magdalie and Nadine, her cousin-soul-sister; they will feel the pressures of the uncle who takes responsibility for Magdalie; they will identify with Magdalie’s difficult relationship with her late manman’s employer.

As the story unfolds, readers watch Magdalie’s struggle to hold on to hope and will feel her weariness as the odds against her continue to mount. While there are many humorous and charming moments, there is no sugar coating here; life is portrayed as what it is for most Haitians: difficult. Offered the chance for love and a simple life, Madgalie doesn’t take it. “I don’t have space for simple love in my heart or my head, at least not yet. It would have to fight with anger and fear and sadness, and, some days, anger, fear and sadness are still winning.” Some days, yes, but not all. Magdalie’s unquenchable spirit begins to heal as she discovers an unwavering truth of Haiti’s people: fòk nou voye je youn sou lòt. We must look after each other.

In her conclusion, Wagner presents a Haiti of the future—the one that every person whose heart beats for this beautiful country wants to see. It’s not mindless, utopian daydreaming; it’s what Haiti can and should be. But in between this closing vision and the opening of the novel on the day of the earthquake, Wagner has created a gem that every reader will enjoy.

If you’re reading this, you’re connected to Haiti, and these two novels will deepen your love for the country of our hearts. Kenbe fèm, pa lage, zanmi m yo.

Written by Sylvia Elias on Wednesday, November 30, 2016